Menu

Vintage Mannequins

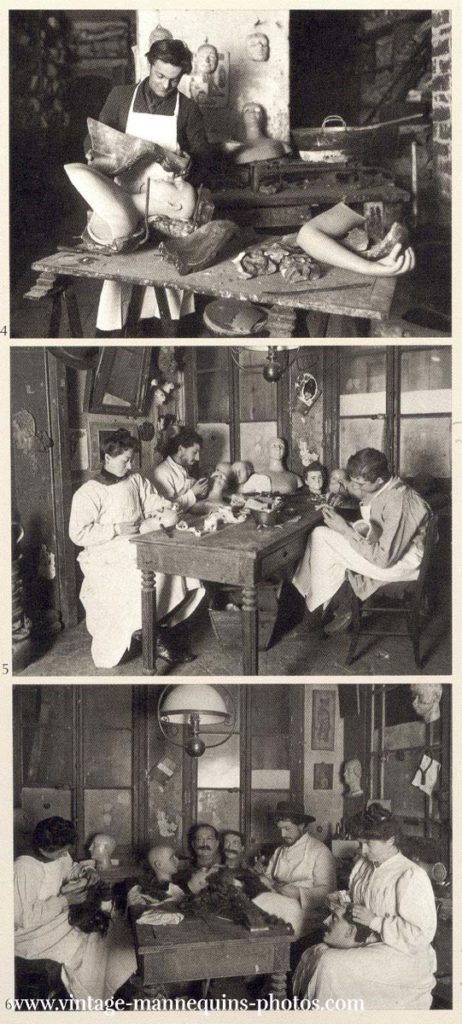

Early 1980, a Cologne antique dealer asked me for the first time to restore a mannequin from the 1920s for her. This would not be the only one. As with every new task I had to start becoming familiar with the new subject. The mannequins often arrived at my studio in a pitiable condition: at times hopelessly broken-bloated from humidity, chapped. The different materials and last but not least, the contemporary make-up were a continuous and interesting challenge.

Each mannequin - whether a bust, head or complete - required a fashion representative of its time for individual treatment.

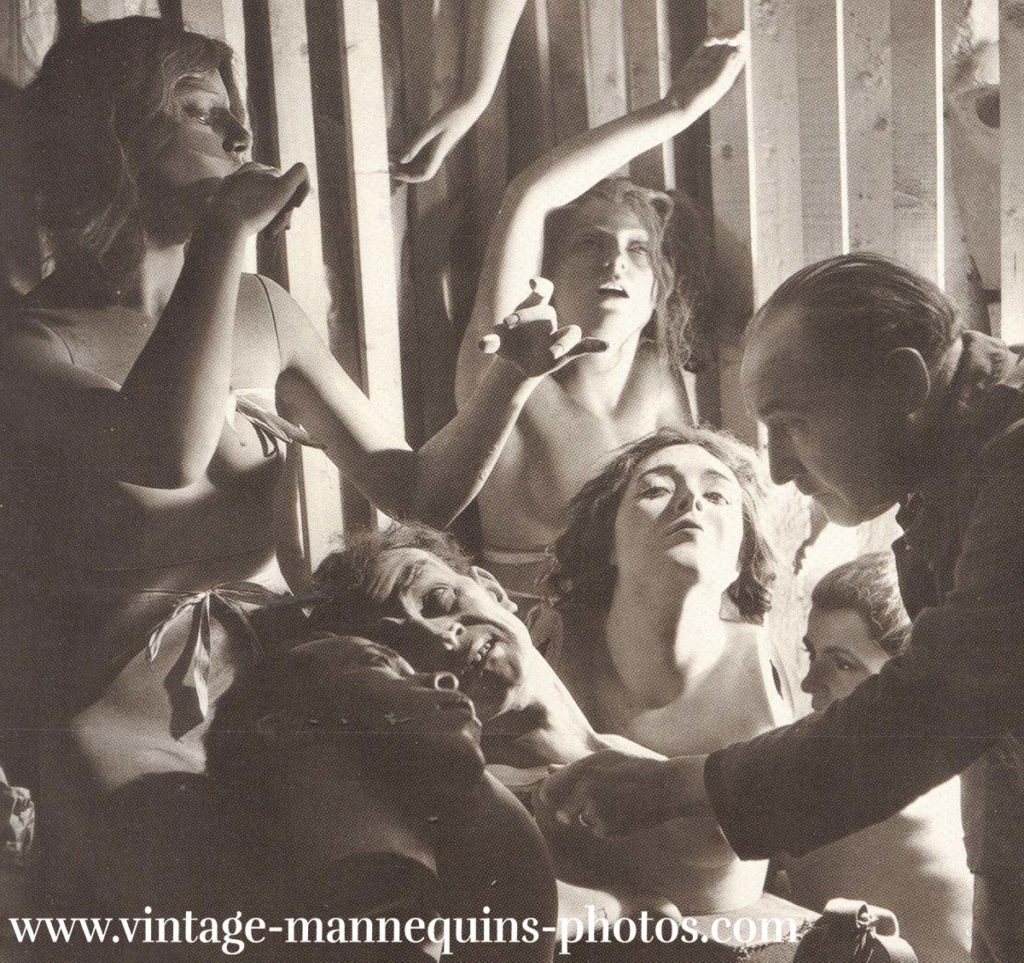

It takes a high degree of experience and historic knowledge to research whether the colours of the damaged piece are original or were changed at a later stage. The first step is to repair the damage by fixing, stabilizing, glueing, patching up, jointing sand remodelling missing parts using sandpaper and smoothing out. The most difficult part of the restoration is the face. Here you have to work with colour, thin brushes and the finest airbrush techniques: depending on the time, - features are highlighted.

Mouths are formed into pouts or little hearts and eyebrows are transformed into bold curves in order to enhance the eyes. I have restored figures made in 1900 through to 1960. Even busts made of wax with real hair and glass eyes, from around the turn of the century. Sometimes they were completely broken. Wax cannot be glued, a soldering iron has to be used for this.

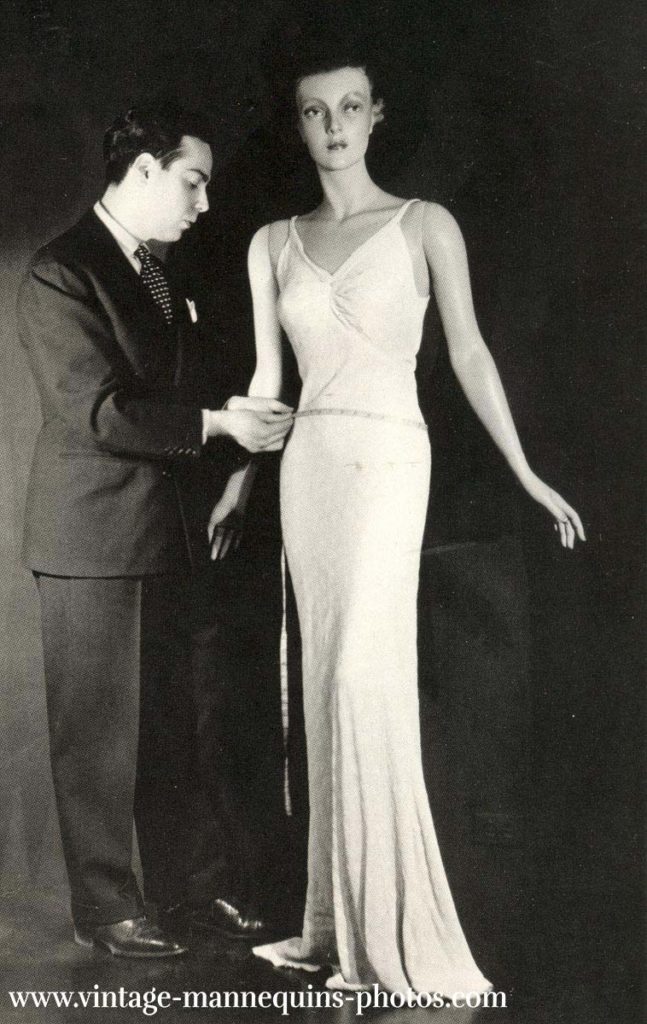

For clothing fashion, life-size figures were needed. Jewellers, hat makers and hairdressers usually needed models. Since clothes, lingerie, jewellery, hats, hairstyles and make-up are dictated by fashion, the figures and busts would become old fashioned and were regularly thrown out. Type, figure, make-up and hairstyle did not conform in with the latest fashion trends and with the current ideal of beauty. So they were replaced by the latest mannequins. Only very few of them ,survived' and were then rediscovered in attics, basements or storage rooms in Spain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany fifty to eighty years later. The long time in exile left its traces. Often quite rotten and in a deplorable condition, they then found their way to my studio.

The French term “mannequin” describes a simple coat stand in the shape of a tailor `s dummy. It derives from the Dutch ,maneken' which means something like ,little man'. Today mannequins parallel to the English model as a professional presenter of clothes. wir heute – parallel zum englischen Model – eine professionelle Kleidervorführerin.

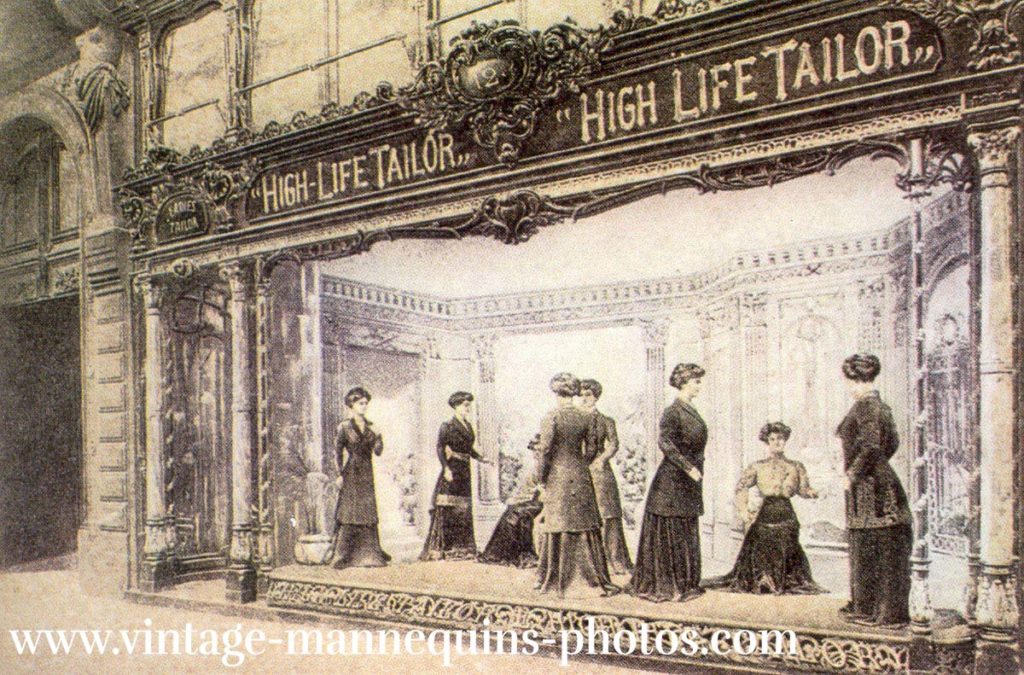

Mannequins as such only appeared when fashion - in the time of industrial expansion - developed into a thriving business and the big department stores were founded in the large cities. Emile Zola reported on over 500 department stores in the year 1860 and wrote about large display cases situated at the same level as the pavements. The first couturiers started their businesses concurrent with quick progress in the ready-made clothes industry - a German, or rather, a Berlin speciality! The made-to-measure technique was also a German invention. Designers won the upper and lower middle classes as regular customers and managed to turn fashion into one of the most important industries at the end of the 19th century. It had a potential for growth that many industries of today can only dream of.

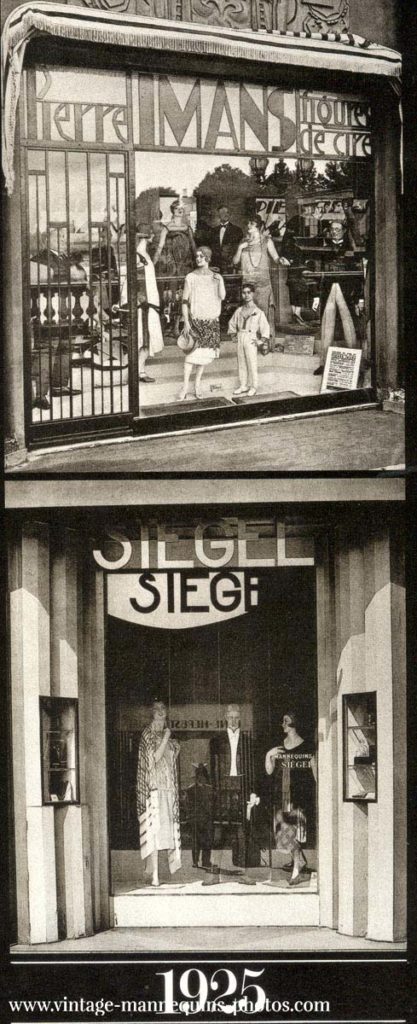

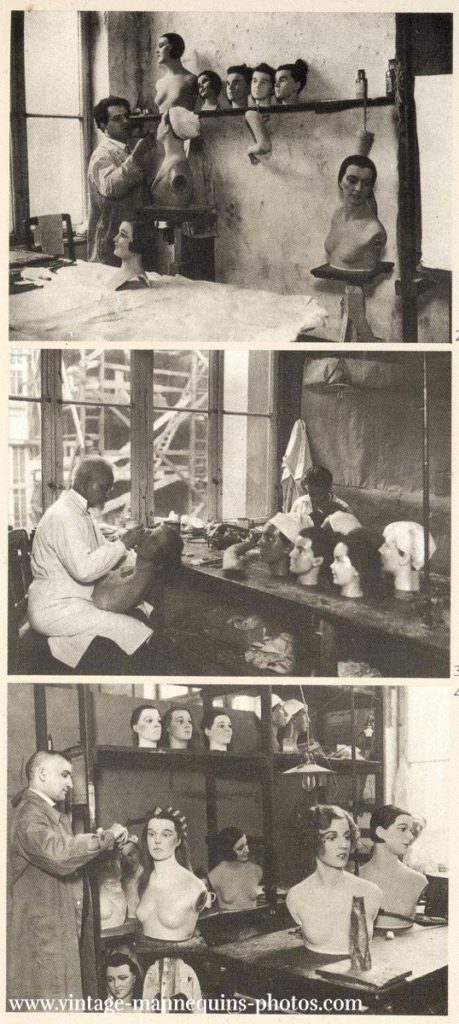

At the end of the 19th century, mass production started all over Europe. In Paris, Brussels, Berlin, Rome and London workshops were set up with as many as 300 cutters, seamstresses, wig makers, wood carvers, painters and varnishers. Workshops - for instance like, "Pierre Imans”, “Siégel-Paris”, “Création Novita Bruxelles”, “Figuren Kralik”, in Dresden, “Werbeplastik Ludwig Klasing Bremen” or “Figuren Moch” from Cologne, used to manufacture figures from wax, paper maché, a mix of chalk and glue from bonemeal. The faces sometimes had glass eyes, and real eyelashes and hair would be inserted one by one into the scalp (made from wax and later from plaster-gelatine) just as in the laborious manner of manufacturing wigs. In one case, they formed the eyelashes from delicate copper wires.

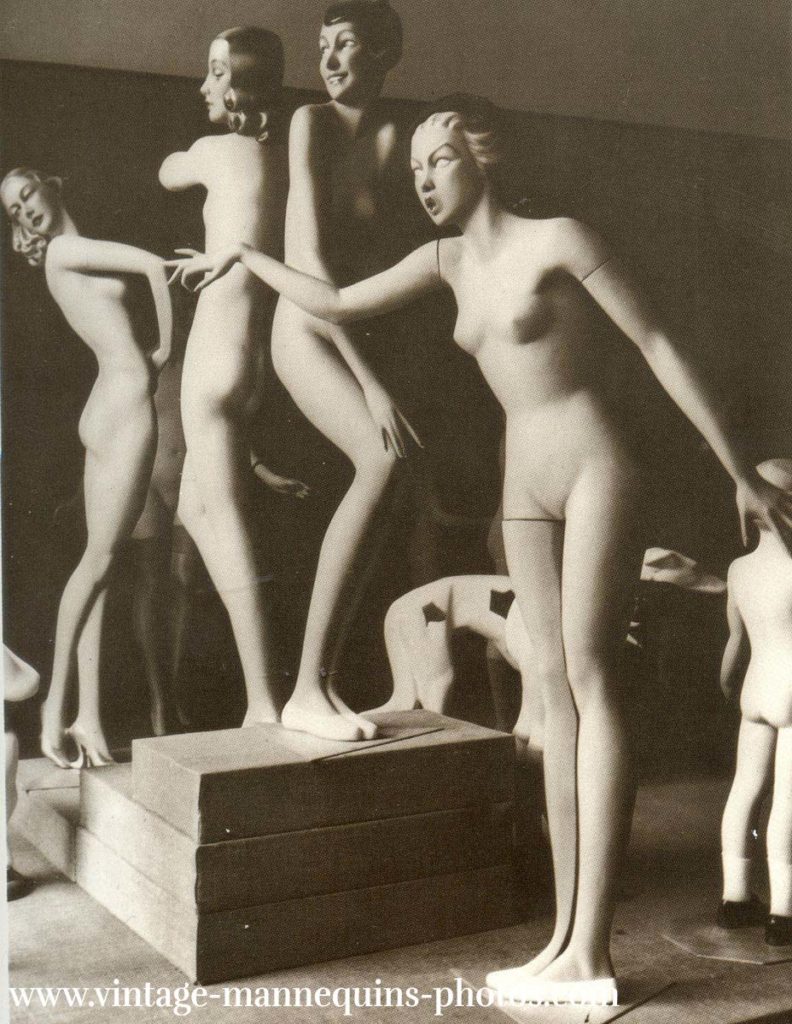

Mannequins demonstrated a variety of characteristics: the sweet-devoted, the self-confident, strong or the snooty arrogant. Sometimes one is reminded of figures by Amedeo Modigliani or by Oskar Schlemmer. From 1950 a lot of new materials were tested. The mannequin made from plastic was eventually born and has prevailed due to its lightness and because it is malleability.

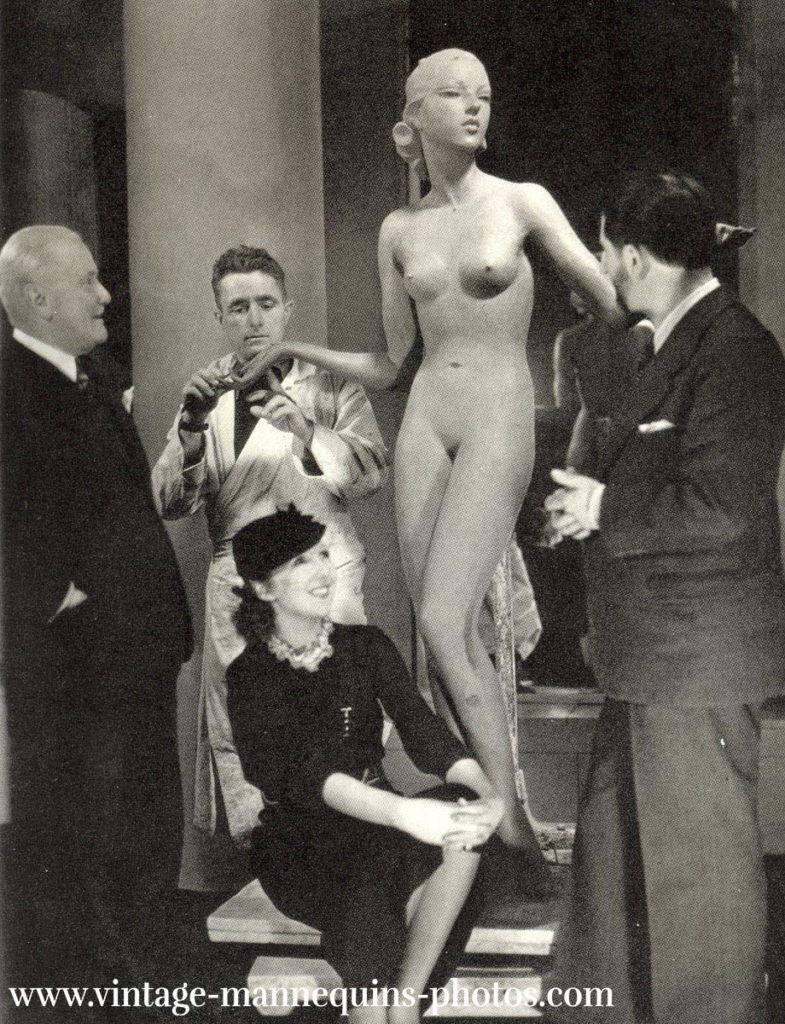

The Dutch model maker Pierre Imans was one of the most famous manufacturers in the first half of the last century and the only one who signed his models. He too worked for many decades for the workshop “Siégel-Paris”. His faces are works of art:: beautiful, with life-like expressions but also stylised, aloof and androgynous.

The main attraction at the world EXPO in Paris in 1900 was a wax figure created anatomically true to life. that he had Imans was influenced by the Japonism, a brief fashion trend of the 1920s.during a brief fashion. His figures were striking because of their elegant and subtle silhouettes and their long and slender hands. He was known for including features of famous people from politics, theatre and film in his figures which were either female or male. Mannequins in shop windows displaying the newest designs and thereby stimulated the world of fashion.

In New York Lester Gaba created a series of mannequins resembling famous film stars of the time, e.g., Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Brigitte Helm or Clarke Gable. It seems that after the “roaring twenties” the thirties was a time of romanticism bewitched by one's dreams of devotion and passion. Lester Gaba fell in love with one of his creations, he called Cynthia, and he appeared with her in public, at the opera and clubs.

Anita Berber (1899-1928) the revolutionary dancer of the twenties, danced to her own choreography in Berlin with a mannequin which awoken of its stiffness, came to life and danced

In Germany the first companies for mannequins were founded shortly before 1900. The figures did not originate in established companies, but were on the whole from workshops or studios of tinkerers and artists. Every figure was created individually and carried the personal signature of its creator.

The industry's success peaked, however, in the 1920s and 30s. After the terrible World War 1, fashion turned into a lavish celebration by creative people where artists, movie stars, dancers, advertising people and above all the modern self-confident woman freed from the corset, dancing together. The mannequins in the window displays where fabulous. The director of the department store Lafayette let artists, such as producer Fred Stockman, design from real models as well as from drawings by modern artists. In 1925 when the fashion industry, along with modern industry and well-known artists celebrated their prominence at the Expo in Paris. The fashion magazine VOGUE talked about ,L'art du mannequin’ the art of the mannequin. Never again has the fashion industry, in Paris or in Berlin, been so closely interlinked with cultural life.

It is interesting to note that Emile Aillaud, the architect of the Haute-Couture-Pavilion at the Paris EXPO, gave the young sculptor Robert Couturier the order to design mannequins in 1925. The result was a scandal at first because the heads were nearly faceless. An enthusiastic female audience however, applauded: 'We like it because each of us can place herself there'.

The mannequin as a photographer's subject was a central theme for many surrealists, e.g., in the art of André Breton, Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, Man Ray and Juan Miró. For the ,Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme' in 1938, the surrealists staged a “Street of Mannequins” populated by their absurdly designed, hybrid-like mannequins. Surrealism plays with the mannequin's suggestive power of seduction. Man Ray was interested in the confrontation of mannequins and people. For Edward Steichen, the main photographer at VOGUE magazine in the 1920s and 30s, the models were no longer mannequins wearing clothes, but rather living characters. This was revolutionary and could only be accomplished by a photographer who was an artist.

I was enthusiastic about each new mannequin and not easily parted from them as they dominated my life and daily routine for weeks. Through the intense work on them, they acquired a soul and a characteristic name. Even in their damaged condition, the faces and bodies radiated a very specific fascination. I photographed them among flowers, bushes and trees. With the time, a varied documentation of their development emerged. Most of them disappeared in private collections later.

The mannequin of the first half of the last century is indeed a cultural asset that keeps on disappearing from the scene. Literature and photos are rare. I am amazed how unknown the mannequin has become as a reflection of its time and a portrayal of the customs and morals of their respective eras. But I am also pleased by the enthusiastic response of men in particular - at my photo exhibitions, men stood grinning in front of their aesthetic ideal or were completely indifferent to one or the other beauty. Woman of refined elegance, unapproachable ladylike, cheeky, daringly self-confident arrogance or the well behaved manners of a conservative bourgeoisé. In any case the topic still generates interesting discussions about the different types of woman and men of past and present times.

I collected all these pretty LOST BEAUTIES , to rescue them from entirely disappearing entirely into oblivion.

2021

Helga Heubel